The true history of Twitter

I pulled into Amherst on a Friday night. From a payphone at the edge of the common, I called my friend, but he didn't pick up, and I realized I didn't know where he lived.

The air was hot and muggy. Mosquito wings refracted in the headlights of passing cars. Down Main Street light was spilling out of storefronts, and there were people on the sidewalk, and I walked toward them and into a bar.

There was a tub of beer bottles floating in ice water, and I drank one almost in one go. He carded me for the second beer. The old wooden barroom, doors open to the night, was packed with people, most of them young. They wore baggy pants, and some of the girls had on short tops that showed their bellies and the tops of their hips.

A man at the bar started talking to me. He was about the age I am now, maybe a little younger. He wore a white polo shirt and was drinking from a small, stemmed glass.

He asked where I was from, and I said I'd driven across the country to help my friend with his software company, but he wasn't picking up and I didn't know where he lived.

"You just drove across the country, and you didn’t have anywhere to go, so you walked into a bar?"

"Yeah."

"Do you want another beer?"

I tried calling Evan again. I could hear the bell inside the heavy, touchtone phone as the bartender lifted it clear of its cord and stowed it away.

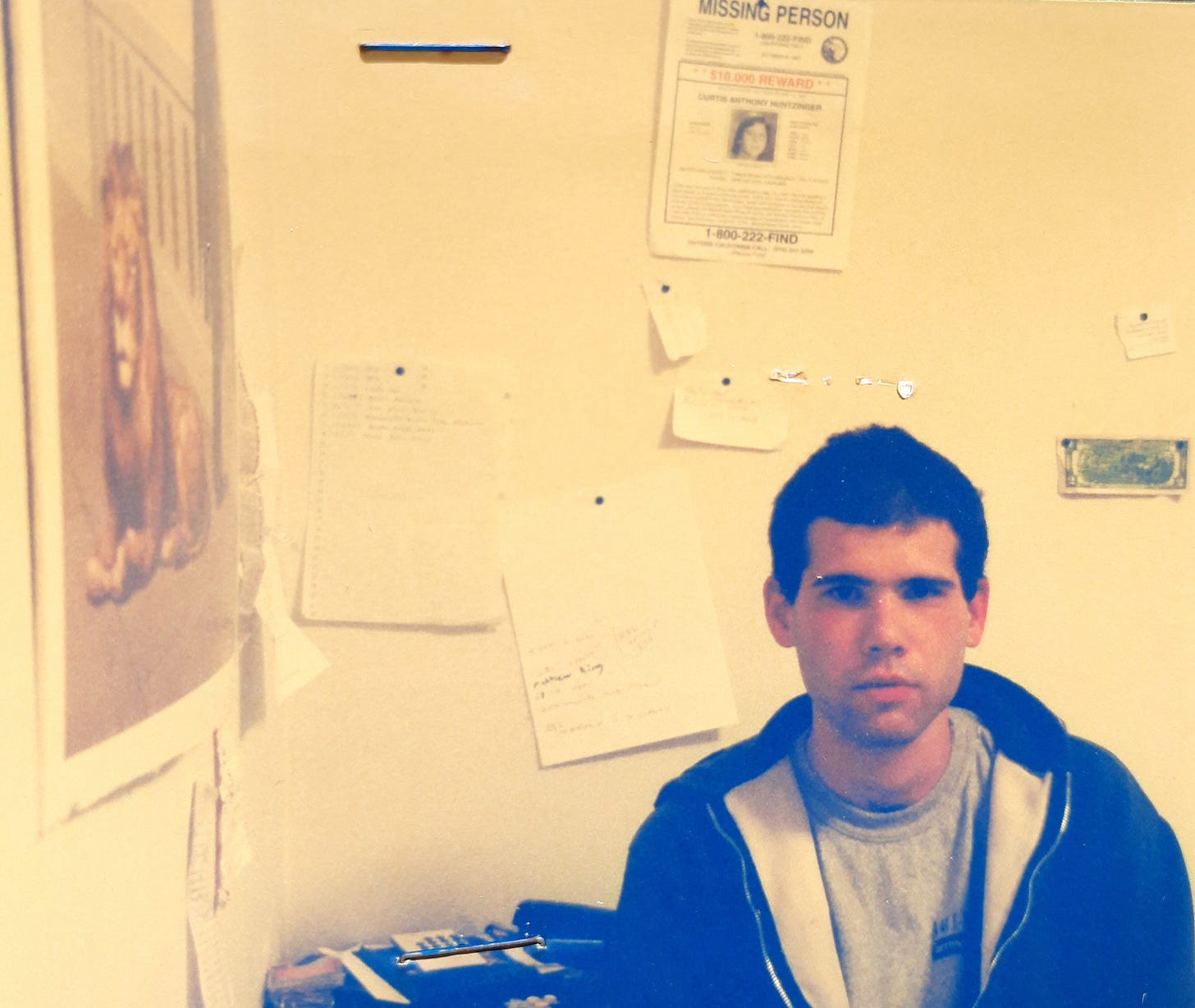

Evan Henshaw-Plath. History has him down as the original lead engineer of the company that became Twitter. That's about to happen, not far from here, this sweaty tavern in the year 1999.

We grew up across the street from each other in Goudi'ni/Arcata. He was a year and change older, and I was fascinated by his projects, which he tackled with single-minded enthusiasm, building a spaceship out of an old potbellied stove, or digging a hole in the basement.

We lived on a street of old wooden houses, tall trees, and droning lawnmowers. As soon as my legs could carry me, I was over at his family’s house all the time, to get some relief from my own. Their house had dark woodwork lathed by a previous generation near the ceilings, and near the floors a maelstrom of toys and objects that were soon to be pressed into service as toys.

Evan's dad, George, had a marvelous leonine mustache. He'd attended an English public school and spoke with a beautiful crisp accent. Evan told me he was distantly in line to succeed the British throne, although there were complications related to injustices against their ancestors. Joyce, Evan's mom, kicked him out of the house when Evan and I were still small. The house became a haven for neighborhood kids, and sometimes other single moms and their kids who needed a place to stay.

Joyce had phone skills. If someone called looking for a woman who didn't want to be found, Joyce would smile into the receiver, stonewall, misdirect, lie, bluff, intimidate, and, if she had to, drop the precise coup de grace of moral fury she'd had ready the whole time. The sound, through the line, of a man fumbling the receiver as he hung up.

If the caller was a parent checking on a kid, or whose kid had come home bloody from the running, semi-serious war between shifting factions of neighborhood kids that was our ground state of being, Joyce would cuss us like a sailor until we were quiet, and then, picking up the receiver, would say the kids were fine. Wonderful, actually. Engaged in some educational activities at the moment.

One of the neighbor girls busted the side of Evan's face open with a brick. He called me and asked me to come over when he was back from the ER with stitches, and equipped for his convalescence with an unlimited subscription to America Online on a new home computer. He wanted to share the rush he was feeling, of opiates and connectivity.

After his head injury, Evan spent a lot of time in his room with the blinds down, hacking an evolving series of computers, listening to NPR sometimes. By then I'd found a new place to hide, a used bookstore downtown, built in the shell of an old bank.

The dome of a head, face lowered, eyes lost behind transition lenses and white eyebrows, pipe smoke in sunlight broken by the shapes of potted plants in the atrium. The building is from a time before architecture adapted to electric light. He's listening to classical music on a magazine-fed turntable, and only barely notices when you come in the store, the stately doors of the old bank. Cats range around him in erratic orbits, through handmade wooden stairways and cubbies. Other customers, if there are any, pick up the vibe, and no one ever enters a cubby someone else is in. You can sit and read as long as you want, with the voices of thousands of years waiting quietly around you.

He didn't stock porn or hate but there was so much else, as the private libraries of the college town ebbed and flowed through the cubbies: pulp sci fi and fantasy and cyberpunk, slim volumes printed by west-coast poetry presses, military and counterculture history, mysticism manuals, underground comix, fanzines, early self-published role-playing games, compendiums of old political cartoons, forgotten tomes with hand-cut pages and print you could feel with your fingertips, no jacket copy, no blurbs, no way to know what was in them but to read the pages.

In all the years I spent in the store, I only remember him saying something to me once. He tapped the paper cover of a book I was buying with his finger as we stood at the counter. He said, "You're reading Elie Wiesel. Good."

I let the guy in the white polo buy me a beer. He told me he was wrapping up his life, getting ready to enter a monastery. Really? Really.

"Seven Storey Mountain," he said. "You should read that book. I dare you to read that book."

"Do you need a place to spend the night?"

I glanced at the bartender, who was half-listening to our conversation, and he relayed the information I needed with his eyes, 'Yeah, he's a regular, I know him, he's ok.'

We walked a few blocks to his apartment, on the ground floor of a nice complex. I can't remember his name now. We sat on the patio and drank beer and smoked cigarettes as the night got pleasantly cooler. He told me about his struggle with faith and decision to devote his life to spiritual practice. I said I was a reporter and it was hard for me to kick against the pricks, because the public service mission of the newspapers I'd worked for was actually the public face of a commercial mission, and decisions about what people did and didn’t get to know flowed from that. So now I was going to try something new, get in on this internet thing, see what that was all about, maybe start an internet newspaper.

We went inside and he went to his bedroom and I lay down on the couch, and we slept like monks. In the morning we drank coffee and ate bread and oranges and filled the sunlight over the table with cigarette smoke. I showered off the road, and when I came out, he was sitting at an old upright piano, painted white, that was crammed into a corner of the living room, and he played.

I'm sure I haven't heard it again. There was sheet music on the piano, but he didn't turn the pages. There was space between the notes, and like an old song it was all melody, translucent music with sunlight pouring through.

I called Evan again and he picked up. I walked back to the common and got my car and drove over to his place, which wasn't far. He was living on Pleasant Street, an old saltbox quartered into rentals and painted gray. He joked about the way the town named the streets as north or south of Main, and abbreviated the street signs, so depending on where you lived, it was either 'SO PLEASANT' or 'NO PLEASANT.'

His apartment was almost empty, hot sauce in the fridge, a mattress in the loft, a laptop charging on the carpet. I put my sleeping bag down in a corner and we took his car to the MetaEvents! office, which was in a new development near the Stop 'n' Shop in Hadley. He led me through a labyrinth of offgassing corridors to the upper floor. All around us, the eerie made emptiness of the unused commercial space. People must have stocked the vending machines and maintained the floors, but I never saw anyone in the building except the guys in Evan's company.

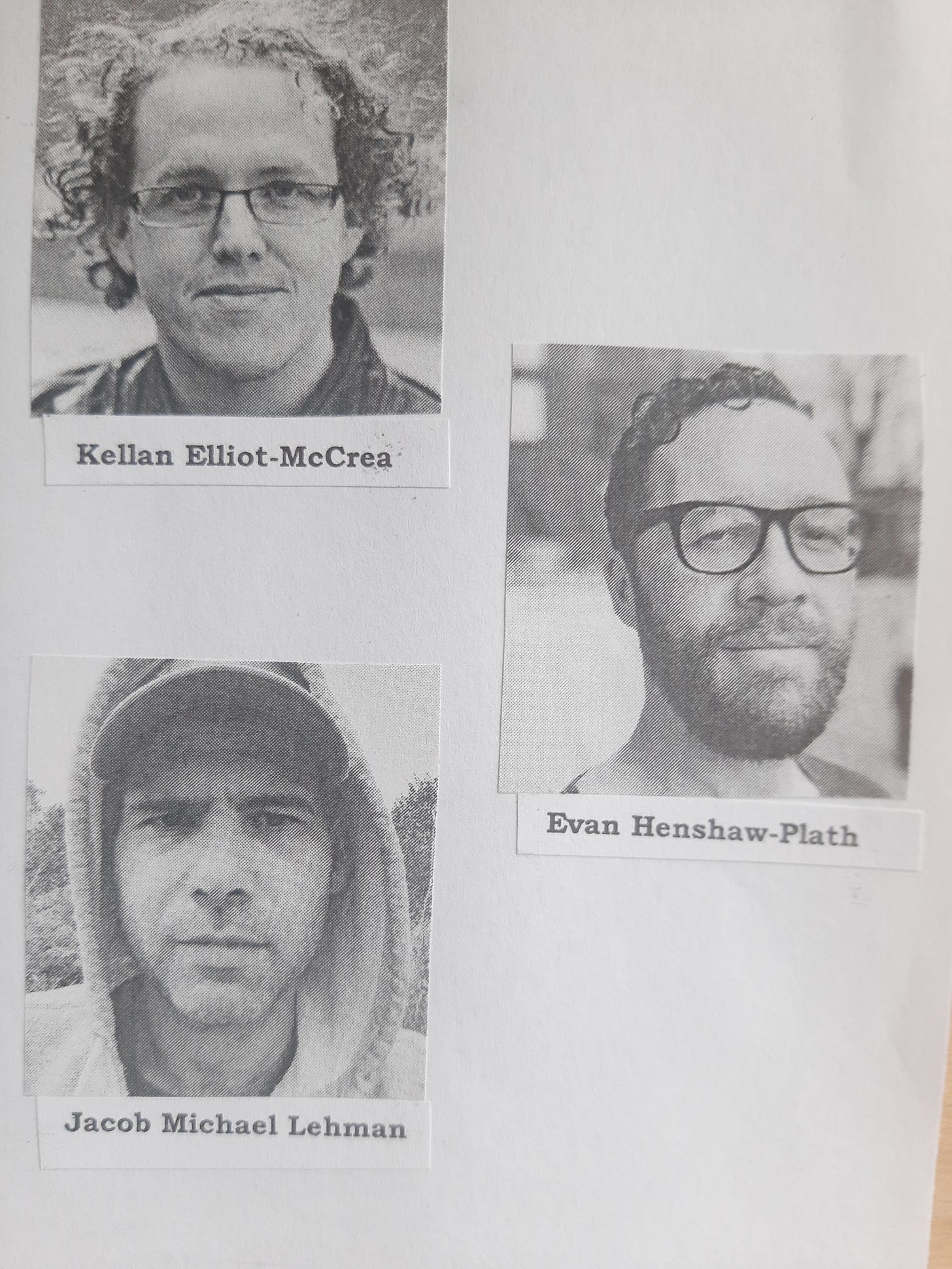

Two of them I knew already, Gareth, with '90s sideburns, and Kellan Elliot-McCrea, with a big three-dimensional head of hair, and there may have been one or two others, from computer science programs at nearby colleges. The office was one rectangular room, a conference table in the center and computers on tables along the walls. One wall was the edge of the building, and a bank of windows looked over the gentle greens of the Pioneer Valley, small fields, lines of trees, traces of sprawl. To my horror, I discovered there was no coffee for the coffeemaker. They offered me caffeinated mints as an alternative, and I ate too many. The next day I bought coffee and filters and cleaned out the machine.

We sat down at the conference table and had an intake meeting. Kellan asked me what I wanted to work on. I said I wanted to make software to put a community newspaper on the web. At the time you had be able to code to update a website, which was something very few editors, who were already, so to speak, specialists in writing code for humans, knew how to do. But if you had software that was easy to use, and easy for readers to read, you might be able to dispense with the dead tree edition altogether, which was by far the biggest expense and barrier to entry in the whole enterprise.

Evan and I said we'd work on it together, he'd think about the software and I'd think about the interface. He maintained a website on the side called Protest.net, which announced anti-globalization marches all over the world, and which he was getting tired of updating as more people sent in content. That was what the web was like back then, you waited for a page to load to see if it had been updated. He wanted to code a way for users to add their own updates, he was already thinking about it from that direction.

Don't worry about the money, Evan said, there'll be plenty of money, it's really about the stock options. They could write me in next round with the bean counters.

We never had a drink together. Most of them didn't drink or smoke, except Gareth smoked Parliaments. Evan was a teetotaler, or a Mountain Dew totaler more accurately. Their drug of choice was in the computers along the walls, and they introduced me. Civilization II: The Test of Time. My experience with video games at that point was mostly as pieces of furniture you put quarters in, or console games that attached to a low-definition TV. You could beat them by memorizing patterns in the software environment and behavior of the automated enemies. But Civ took you deeper, deeper into the machine, if you will, a mentally immersive environment such as I'd never experienced. It seemed real enough when you were in it, and while you were, nothing from the outside world could matter, which for me, and I suspect, others, was accompanied by strong feelings of relief. I've been addicted ever since, and have used versions of the game off and on, sometimes for days at a time.

The room hushed, overhead fluorescents off, blinds down against the summer light. Young men checked out of their bodies, mentally welded to the terminals.

The company wasn't about forcing production, doing just to do, it was about making the space to really come up with something. And the null space of the game, or surfing conceptual art websites, or doing whatever, without intention, was part of that. In my memory it was Kellan who set that tone, his laid-back California cadence integrating terminology from his east-coast education. Don't let anything I say persuade you these weren't all very intelligent and perceptive guys. They were out for a big win on the electronic frontier, and they didn't trust conventional means to get it. There were no conventional means, anyway.

In the mornings, while Evan was asleep, I'd walk to a cafe and spend the money from my most recent reporting job on a ruinously expensive spread: a locally-sourced Danish, fair-trade coffee, and a crisp New York Times, and I'd smoke and read the paper in the sunny courtyard of the cafe among the chic denizens of Amherst.

On the drive to work one morning, Evan mentioned that Gareth had Heather's new phone number. When we got to the office I got it from him.

Heather. Go back three summers and draw a card. She was a physch major at Hampshire College, wanted to work with adolescent girls. One of the first times I saw her, not the first, but one of them, she was sitting cross-legged on a picnic table in a quad of one of the dorms, surrounded by other students, admirers, men and women. She's laughing, her eyes are almost black, her long hair flashes where the wind and sun catch it together, and the whole circle, all around the table, are all trying to talk to her at once, she's turning her flashing head to share it with each of them.

I never would have had the guts to talk with her if I'd known how beautiful she was, but I didn't, because we met online.

Late spring of the year I turned eighteen. I'd left home for the first time and was hitchhiking around the country. And like I did when I got tired, I went over to Evan's house. He was living, not in a dorm, but a "mod," a campus apartment shared with four or five other students, and a living room couch to crash on, at the edge of Hampshire's sprawling grounds, where there were old oaks and crumbling stone walls in the woods. Squirrels everywhere. Evan was playing an away game with Hampshire's ultimate frisbee club, The Red Scare, and I had his room, his desk, and his keyboard to myself.

Sunlight soaked the room through a big, clean window facing east toward campus, but you couldn't see the buildings, the modern tower of the library in the center, because of a rise of bright green grass and a few big oaks. As a hacker courtesy, Evan left me logged in to all his accounts, and I was exploring a chat server called Hamp on the campus intranet. It was different from anything I'd experienced because it was so much faster, practically instantaneous, which made a huge difference conversationally, chats over modem tended to take on a double-helix structure of each person replying to slightly obsolete replies. I could type faster, and more gracefully, than I could talk, so for me the speed of the intranet was like a pair of seven league boots. Heather and I made each other laugh through the machine, and then we met in person and smoked some cigarettes like cool '90s kids, and then Evan said his modmates kind of wanted their couch back, and Heather said I could stay in her dorm room.

I lost what I'll call my voluntary virginity with her. Sex, especially then, produced a strange reaction in my body. What would begin in pleasure would quickly change to frozen trembling. I didn't think about where it meant I'd been, I just thought there was something wrong with me. Heather lay down beside me on the dorm room floor, kissed my cheek and held my hand. I don't remember what she said, but I remember the kindness in her voice, and she led me past where the ice melted.

She'd been in love before, she wanted me to know that, a steady boyfriend in high school, the singer in a grunge band. She had other suitors, but I felt what we had was deeper. I don't know, maybe it was because I felt safe with her. I went back west, applied to Hampshire, wrote my essays, and got my transcript. I’d gone to a small alternative high school held in a disused elementary school on a spit of Humboldt Bay. Evan went there too, we were more rivals than friends in those years, and played tackle football on the beach with some of the other kids just about every lunch period.

I went to see my civics teacher to get a letter. Tutor, I should call him, I was the only kid in his class. John A. Jackson was his name, he lived in an apartment in Trinidad with Pam, his wife. They’d worked for small newspapers in southern California for most of their lives. John was near the end of his watch when I knew him, retired to a weekly column, his body destroyed by tobacco and cola soda, the lifelong stimulants of his mind. One bedroom in their otherwise neat apartment was choked with books, boxes of files, stacks of loose papers, and loud, bulky computers and modems. Maybe a half-played game of kriegsspiel competing with everything else for horizontal space.

You might think you live in a democracy, he taught me, but you don’t, you live in a republic. Franklin called it and that’s what it is. There’s only been one democracy, and that was ancient Athens.

Wait, I said, what about the Iroquois? The Althing? Burnaby’s Code?

Ok, fine, he said. Athens is the one I know about. But let me tell you about Athens, because it’s worth hearing. They were different from the nations around them, because all citizens held sovereignty, and when they made decisions they got together in an amphitheater, as a city, as a country, and talked it out, sometimes at great length, and when they had to, they voted. He held up his hand, I know you’ll object to this next part, he said, but hear me out. Citizenship was limited to property-owning males. And some of the property they owned or believed they owned was other people. And that was probably their undoing, because the rich men in the amphitheater lost touch with the actual conditions of the country’s farms and military.

John thought the problem was they just didn’t have a big enough amphitheater. If they’d listened to women, to workers, to soldiers. Listening to people, that was his newspaper creed. He told me when he was an editor he used to let the homeless come into his office, sit by his desk, and tell him their crazy for hours.

“Why did you do that?”

“It was my job.”

He was crazy about the nascent internet, which he called the “World Wide Wait.” Because now we finally almost had it, see? An amphitheater big enough for everyone.

When I went to see him to get a letter of recommendation for Hampshire, he asked me, in his earnest newspaper way, “What is it you hope to find there?” His eyes were clear gray. I said whatever I said and he wrote whatever he wrote but later, after I’d gotten an acceptance letter for the spring semester and was packing up to drive to school, I had a dream that was like a deeper answer to his question.

A summer night, the black sky of late summer, all the stars clear as life. The green muggy heat of New England around us, green grass, like and not like a football field, like a bowl, all grass, with a fire burning down in the center, and there were lots of people around, kids my age, mostly, in groups or talking across groups, some of them sitting on blankets. Like a music festival, but with a different energy, they were here, we were here, not for a show, but for each other.

A kid by the fire started speaking in a clear voice that filled the bowl, and people turned to listen. Then it was someone else’s turn. As the speakers who had finished made their way back uphill into the crowd, we felt like we knew them, because we’d heard them, and there were backslaps and handshakes and hugs. My turn came and I went down by the heat of the fire and said what I had to say, and was embraced as I had embraced others, and we knew each other, and the city knit itself together.

That summer I went back east to see Heather, I rode freight trains with a kid I met at logging blockade in Oregon who called himself Marlow, who turned out to be a student at Amherst College. Heather was living in an apartment in Easthampton with another student, waitressing, working two or three jobs, trying to make as much as she could. She took a morning shift at Burger King and had nightmares about the machines. I thought it was all right to hang out and read library books and play video games at the pizza parlor while she worked. From an old blue-collar Maine family, she was in danger of being financially maimed for life by Hampshire's tuition. Mine was paid for. Did I really not see she was treading water as hard as she could while I floated nearby?

I think it's more accurate to say I couldn't face it. Money seemed so cruel and preposterous, and damaging to the people who got involved with it. But you have to have it to not think about it, which is part of the cruelty. It's one of the things I wake up at night regretting: that was my shift at Burger King, my share of the rent. If I'd behaved like a partner, I might have won her.

I moved into my dorm room in February, and Marlow invited Heather and I over to his girlfriend's family's house, an old place in Amherst not too far from Emily Dickinson's, not a party, nothing like that, but people from the village might drop by, it was that kind of house. Marlow's family was well-established in the valley, I'd stayed a night at their house after our freighthopping trip, it was a well-appointed old farmhouse on land delineated by stone walls, and inside there were original oil paintings on every wall surface. After the train, the people who had nothing who had helped us along the way, I recognized Marlow's embarrassment at his family's comfortable circumstances. I was glad we weren't staying at my parents' house.

Anyway, we were walking through town in the cold night air, at Marlow's girlfriend's parents' house there would be a woodstove in the kitchen and people from the village dropping by, and we would drink beer and hang out. I can't remember her name, I only met her the night I broke my skull, and all memory around that event is strange and lit with pain. But I think Heather recognized the pattern in her sweater, not just what it was called, but what it meant, and they were fast friends, walking arm in arm ahead of us under the streetlamps. Marlow was sporting on the sidewalk ice, running and sliding, and I joined in and flew into the pole of a street sign with my face.

We got to the house, there was a fire in the woodstove in the old kitchen, I took one sip of beer and felt very bad. Heather drove me a long way to find an ER, it was late by then, we had to go all the way to Easthampton. Closed skull fracture, nothing we can do for it. But the next day a clinic had a new painkiller "that's less addictive."

"You've changed, Jake," Heather said. I spent most of my time in my doom room with the blind down, sleeping or listening to music. Classes intimidated me, more than once I spoke up and found myself saying something foolish. I said something sarcastic to Heather and she broke it off formally.

Marlow came to see me in my dark doom room. He told me gently he was disappointed by my drug use. He said I wasn't respecting my capacity as a person or an activist. His is one of the faces I sometimes think I see in a crowd, but of course he wouldn't have the same face now.

I kept going to doctors who would say there was nothing they could do, and write another prescription. Eventually the pharmacy flagged me, and I made a jagged transition to buying weed from campus dealers. There are some friends and neighbors I remember well from that semester, but when it was over, I had no desire to return. I went to western Montana and ended up working for a small-town newspaper.

I waited until Evan left for the office and called Heather's new number. She answered, she was doing well, transferred to a state school, she liked it there, she was with a new guy, it was pretty serious, she'd moved on. We said goodbye and I cried a while and then drove to the office.

Was it that night? Evan came back to the apartment late, when I was already asleep. I dreamed my grandma Giska, who'd died a few years earlier, was crouching over me, gently smoothing back my hair, but of course I also knew it was Evan touching my face and buzz cut and I moved and heard him go up in the loft.

Next night I went back to the bar, but the monk drinking from the funny glass was gone, packed up and gone to join his order, probably. "Yup," the bartender nodded when I asked. That was exactly what had happened. Out in the crush of the street, I found a weed man in front of a cafe. Flat brim hat, gold grill. He pushed the bags into my hand. Sweet.

"How's your night going?"

"How's yours?"

"Want to smoke one?"

I miss that since Covid, and maybe it'll never be the same again, like sex was never the same after AIDS, but I miss sharing cannabis and conversation with strangers, the simple pleasure of passing a joint. Or a blunt, excuse me, Willie smoked blunts. He cracked me up doing voices, imitating his customers, the college kids, all the bullshit they put him through.

I stayed out in the muggy nights, drinking cold beer dressed in paper bags, sharing the blunts in Willie's circle, buying a bag for the morning. Did I know I was waiting for Evan to fall asleep before I went back to the apartment each time?

One night we were smoking behind the CVS, the same pharmacy that flagged me for opiates during my trainwreck semester. Wait, the cops are here, cars converging fast, lights flashing, the old round halogen lightbars, Willie's friends take off, and here getting searched it's him, me, and a young woman in a stroller who Willie has been pushing around and who seems very high. She's also wearing a fur coat despite the heat. Cop finds my knife, a lockblade I always carried.

"I'm taking this," he says.

"Why?"

"Because it can hurt me."

Our IDs clear and Willie has not a speck of dope on him. We were walking back to Main Street and I said I'd catch up with him, I'm going to the cop shop to get my knife.

Willie looked at me like a snake he'd almost stepped on. I'm not a cop, I said, I'm just not afraid of them because I worked for newspapers. They can't just take your shit, that's the Constitution, and I know it's a legal carry because I looked it up on the internet.

He looked unconvinced.

"That’s a thirty dollar knife," I said.

"OK, Captain America, go get your knife."

I was afraid of him now. We were both still feeling the encounter with the police. He turned back toward me midway across the street.

"Hey," he said. "What are you? Writin' a book or something?"

"No. I mean, I don't know. Maybe. It's possible."

He squared up in his dealer stance, grill flashing in the sodium streetlamp. "If you are, make me look good."

The foyer of the police station in Amherst was a brightly lit glass cube. I went in, picked up the phone, talked to the dispatcher, the desk sergeant came to the window, listened while I asked for my knife, ran my ID again, told me to wait. Half an hour later he came back, handed me my knife. "I don't know why he took that from you," he said.

I saw Willie the next night, no hard feelings, but I bought twice as much and we didn't smoke together. I rolled my own joint and smoked with some kids behind the CVS. "Hey," one of them said to me. He was a local college kid with a Massachusetts accent, and I guess he knew the cops. "They want you to know. Willie's dangerous. They think he's killed people, they just can't prove it yet."

I was almost out of money, anyway. I asked Evan if the company could pay me something, but he said this wasn't a good time right now with the investors, and it didn't help that I was hanging around the office all day playing video games, they might drop by. The next morning I asked him in front of the others if he was ready to work on that project we'd said we do. He was, actually. He'd been thinking about it from his end. I'd been thinking about it myself, mornings at the cafe with the paper, and browsing news sites on the office's superfast internet connection.

We stood at the whiteboard. The others swiveled around to listen. I picked up a red marker. "Ok," I said. I drew the screen of a desktop computer monitor, wider than it was tall. "Here's your news website," I drew a browser window inside the edge of the monitor. "Up here, your name, the date, your motto, whatever you want," a long box across the top of the screen, "display ads over here," a column on the right, "you can crop them out by shrinking the browser window, which is nice for reading, but advertisers still get their money's worth, because local newspaper advertising is mostly an economy of goodwill, people want to see the ads sometimes."

I drew a square in the remaining space. "Here's your news, this is the part that changes all the time. This is the part I've been thinking about."

News websites at the time were nowhere near as pleasant or coherent an experience as reading the paper at the cafe. Some newspapers put images of their print pages on the web, you could walk to the corner and buy a paper before one loaded. Others had headlines you could click on, but one missed or foolhardy click could mean minutes of waiting just to be able to go back and try again, glitchy display ads trying to load coming and going. Watching myself read the paper and browse the web, I'd noticed that the headlines alone weren't enough information to make a good decision about whether to invest attention in a story, I explained. With the physical paper, my eyes would see the headlines, and photos, of course, and when one of them caught my eye, I would scan the first paragraph of the article, called a lede in newsrooms. I told them a lede was supposed to encapsulate the newest and most relevant information in a story, and a good one will generate interest or even suspense to draw readers into the details.

I drew a field of boxes in the news space, wider than they were tall, about the dimension of a newspaper lede on the page, each with a few lines of text inside, each a link to a full story. As an editor, you had to be able to plug in different ledes and stories, and move them around, your most important story in the upper left, probably, where the eye goes first for most people who read left to right.

"And you want to be able to update it from anywhere, right?" Evan said.

"Well, yeah."

"See, I think it should look like this," he took the pen and drew a single column of boxes. "I can tweak Calendrome to do this. The newest update just pushes the others down one."

"But the newest information isn't always the most important."

He waved his hand, "We'll fix that later. This is good, I'm going to work on this." He went back to his computer, started typing.

A couple of days later he called me over to his workstation. He seemed excited. "You can update the stack with a text message," he said. "I think this is a Protestnet thing."

He said he saw it as a tactical tool for protesters, an equalizer. I still wanted software for an internet newspaper, but he said he was too busy with the texting tool now.

I think I called my mom to get the money to drive back across the county, either that or I mooched it from Kellan. I got to California and started working for a paper in Garberville.

A few years later I saw a businessman on TV calling himself a founder of Twitter, and I thought, 'I didn't see you around the whiteboard.'

Despite all the work Evan and others put in to making the idea a reality, I was disappointed that they sold the company without consulting me, and were less than forthcoming about its origin. Because Twitter doesn't have to be the way it is now. It can be civil, secure, and fair.

Please share this text, provided it is complete, unaltered, and attributed, so the true history of Twitter may be know to all, and thank you for reading.

For more information about the people who took control of Twitter, now called ‘X,’ check out my posts on Mastodon.

__